It was my last visit to the village, my last night to sleep over at my friend Jane’s house, and our last chance to visit – Lucas, Maiko, Ashahadu, Jane and I. But, the universe had other plans. Mama Aziza was having her baby! Mama Aziza is Jane’s neighbor, her husband has contributed to our secondary school and their first two children are often hanging about Jane’s house. Lucas and Jane suggested that I accompany Jane to help. Help? Um, I train language teachers…

Having a baby in the village is a highly problematic ‘natural’ phenomenon. As my new friend Gillian put it, having a baby is the number one killer of women worldwide. With no access to proper healthcare or healthcare professionals, the women are just risking their lives, or rather – banking on a smooth delivery. In this particular village, every woman knows several who have died in labor. Our night watchman’s wife died two years ago, followed shortly by his brother’s wife.

So, as I follow Jane into the night I’m just banking on everyone’s good karma that this mama and her baby will make it through.

It’s 10pm. She’s been in a labor for ‘a while’. I couldn’t get an estimate. Lucas was concerned because she hadn’t delivered yet. I told him labor can vary in length dramatically and not to have any expectations around time. Nonetheless – he was worried and now I was expecting drama.

I didn’t know what I would see. I thought maybe I would go in and Mama Aziza would be moaning, groaning, and pushing – surrounded by women giving her support and advice. I arrived to find Mama Aziza lying on a dirt floor on top of a woven grass mat. Beneath her lower body was a plastic bag spread out over a burlap sac. The room was lit with a small kerosene lantern – open flame; no fancy glass cover. It shed light on a 3 foot diameter at best. In one corner was Ashahadu’s mother, Mama Nasula – resident Midwife. She was lying on a grass mat, too, just keeping watch – waiting. Along the same wall as Mama Aziza were two elder women – one was Mama Aziza’s mother and the other was another seasoned baby catcher.

I knew this would be an interesting night when it struck me that Jane’s English really stops at the basics and no one else could speak English at all. We exhausted my Swahili and Kiha vocabulary in about 20 minutes. Jane and I took a seat on a long bench along the 3rd wall. 6 women, one in labor … sitting in silence beneath a full moon, tucked inside a mud hut glowing by the light of a flame … waiting.

As I sat with the women, I took in the scene. A mud house with an aluminum roof, plastered walls and windows with screens and iron rods. Cardboard and curtains keeps the light and peepers at bay. On the wall above Mama Aziza’s head was a spider the size of a lily pad! No one was phased by it and several times, when talking or waiting, each of us looked up at it – acknowledging its presence but not even noting it to one another. Later in the night, when I realized it was no longer by Mama Aziza’s head, nor did it climb up and out – I started to wonder whose skirt it would crawl up … that never happened, and I saw it depart the scene after the baby was born.

Mama Aziza was the most quiet woman in labor – not that I’ve seen many and Hollywood probably exaggerates. She would simply turn to the wall and place her palm against it, sometimes putting both hands behind her neck. None of the women moved to soothe her. At one point, Mama Nasula spread her legs and took a look. She placed the kerosene lantern between her feet and inspected. She had rubber gloves on, but I think they were more for her benefit than Mama Aziza. She kept them on the entire night – moved a bench, moved a mat, closed a door, laid down for a rest, handled escaping bodily fluids, and ultimately, inserted her fingers in some very sensitive areas to help the baby arrive. Sterile? Not so much.

After about an hour of keeping watch and simply noting when Mama Aziza turned to the wall or seemed to be having a bit of discomfort, things changed and she was getting closer. Her pain shot up and she needed Jane to sit behind her and support her. This is when I was asked to sit and hold her leg so she would stay in the right position. From this point, my mind was mostly blown.

Jane moved down to Mama Aziza’s feet to help Mama Nasula. Mama Aziza endured intense labor from this point for another 2 hours. “Sukuma” means Push – I heard this about 400 times during those 2 hours. Mama Nasula has delivered over 100 babies in the village. She is older – in her 60s. She has had 10 of her own children! At some point in time, people from the hospital in town came to the village to find out who delivers babies. They discovered Mama Nasula and checked her notebook – in which she documented all the women she’s ever helped – date, labor experience, baby’s health, mother’s health, etc. Upon evaluation of her existing background knowledge, they offered to bring her to Maweni hospital and have her trained. She has never lost a baby or a mother! She has sent 4 to the hospital when complications arose, but the hospital took care of them.

At one point, Mama Aziza’s mother comes in with a tin bowl filled with some little branches and a bit of water. She swished these branches around, broke parts off and basically made branch soup for about 5 minutes. When she was finished, Mama Nasula took this liquid and poured some into a cup. She had Jane pick out the dirt and leaves, then had Mama Aziza drink it. Then, she drizzled some of the syrupy liquid from Mama Aziza’s belly button – all the way down. I figured it was a traditional ‘activator’ of sorts. I think the biggest fear in the village is that the baby won’t come or that it will be in breech position. This is scary anywhere, but considering a car can’t arrive from town for about 40 minutes, with a 40 minute return to the hospital, you really can’t get that close and then hit the wall … time is not on their side.

As the contractions got closer and the pain intensified, Mama Aziza’s body also indicated the time was upon us! It was pretty amazing to see her open up and prepare to release this little child into the world. As she pushed, they wrapped a kanga (colorful cloth the women all wear like wraps, scarfs, slings for babies, etc.) around her waist. It looped under her lower back and the ends were pulled forward inside her legs. Jane held one end and Mama Nasula and I held the other. They pulled so hard I thought her lower back must be getting rocked! At this point, Mama Aziza is lying flat on her back. Her ‘job’ is to grab hold of the kanga right inside each leg and use this to pull herself as she pushes. About four big pushes from the end, she wanted to give up. She was hugging her mother’s legs and weeping between contractions. “Mungu Wangu” (“My God”) – she sobbed.

Did I mention there are no pain killers?

Also at about 4 big pushes from the end, Mama Nasula and the other women started to really lay into her. “Sukuma, Sukuma, Sukuma, Wewe! Sukuma!” They were scolding her – Push, you. Now. Push. Ah, You, push push push. There was no word of encouragement and her mother was even a bit harsh, telling her to basically ‘suck it up’. I was being me, which included saying things that I’m sure they found funny, like: You can do it. The baby is so close. You’re doing great. At one point near the end when she stopped pushing and seemed to give up, much to the amusement of Jane, I told her (in Swahili) – – Dada (sister), the baby is almost here. We saw its head and hair! You’re so close!

It was the scariest thing in the world to see the baby’s head crown and go back in and crown and go back in. I thought for sure it was being suffocated or squished. When Mama Nasula seemed worried about the time it was taking for baby to come out, I was worried. Then, when the head came out and Mama Nasula unwrapped the umbilical cord from around its head and tusked with her tongue, I thought – No, No No, please! Not a stillbirth!

Finally, with one last push, the baby plopped out – almost landing on the lantern (which I moved out of the way). It’s a boy! And he’s white! Apparently, that changes quickly.

Finally, with one last push, the baby plopped out – almost landing on the lantern (which I moved out of the way). It’s a boy! And he’s white! Apparently, that changes quickly.

Mama Nasula put her gloved hand into the baby’s mouth and helped clear it of all fluids. The baby started to cry immediately – and powerfully! Mama Aziza just collapsed back, exhausted. Mama Nasula wiped the pasty fluid from baby’s eyes, face, mouth and then loosely wrapped him in the closest kanga and left him lying on the mat, right by my knee. I patted him on the back and made little clicking sounds to soothe him, which the ladies chuckled at. I wasn’t sure what the delay was as they talked among themselves, neither tending to mother or child.

Jane got behind Mama Aziza and helped her into a squat. She sat there with no emotion or reaction whatsoever, staring at the ground in front of her, which was covered in blood splattered kanga and mat. Then, Mama Nasula helped her deliver the placenta … and what else? There was so much blood, something blue that looked like a swollen shower cap and of course, the umbilical cord. Then, Jane stood Mama Aziza up and walked her in a half circle, before sitting her down in the dirt across the room where she feel asleep sitting up. When she was walking, blood poured out of her, so I had my 3rd (?) panic attack, thinking of women dying post partum from bleeding too much. As she sat sleeping upright, the soles of her feet faced me, dimly lit by the lantern. They were streaked with dirt and blood. I was still soothing the baby – really wishing I could pick him up, but feeling ok knowing at least he wasn’t cold.

Finally, after more back and forth and some work with a string, it was time to tie off the cord. The other elder woman came over with a razor in a sterile package. She took it out and checked with Mama Nasula about where to cut. She was corrected and remembered she had to tie the cord first, so she set the sterile razor on the mat between her feet. They tied the cord and then cut it with the razor. Only at this point did all the women (except me and Mama Aziza) start a little tribal ritual of clapping and making great sounds with their voices.

Finally, the baby was lifted and wrapped and handed straight to me. I was hoping this wasn’t another one of those awkward ‘mzungu’ moments where I’m given some honor I don’t want or deserve just because I’m the visitor. It’s happened to me at weddings and other important events. In this case, they just had a lot to do before they could do anything else with the baby or the mother. Mama Aziza and I sat in silence as the women busied themselves around us – scooping all the blood and other bits into a trashed kanga, removing the blood stained mat, using a hoe to clean up the dirt that had been bloodied. Mama Aziza was wiped out. I asked how she was. I told her congratulations. She smiled weakly and zoned out. I couldn’t help but think about how uncomfortable it must be to sit in the dirt, right on her tender lady parts – but she wasn’t thinking about anything. The baby was so calm. He suckled on his own hand and eventually fell asleep in my arms.

After cleaning the birthing space, the women took Mama Aziza out to bathe her. The baby and I sat together for about an hour as the lantern projected our dancing shadows on the wall behind us. Finally, Mama Aziza and Jane came back in. Mama Aziza was freezing. It was 2:15AM and it was cold outside (for the village) and she was wet. Jane quickly got her into a blouse and jacket and then wrapped a kanga around her. Now she was alive again. She looked up at me and said, Asante Sana. I sat next to her and again congratulated her. She glanced at the baby, but still had yet to acknowledge him in any way. The women brought her bed back into the room (an oversized sponge) and set it on the floor.

A few minutes later, Mama Nasula came in and took the baby from me. She did a ritualistic mother-child introduction. Mama Aziza turned her palms up and Mama Nasula touched the baby to her palms five times, saying something in the Kiha language before setting the baby in mama’s hands. Even then, Mama Aziza was too wiped out. I helped her make a bed for the baby and the women brought her in a few pots of food – ugali and beans. Mama Aziza is Muslim. This is the time of Ramadan. Even though being pregnant, nursing or having your period is an ‘out’ for fasting, many villagers don’t break the fast, so Mama Aziza had been fasting. Now she was ravenous!

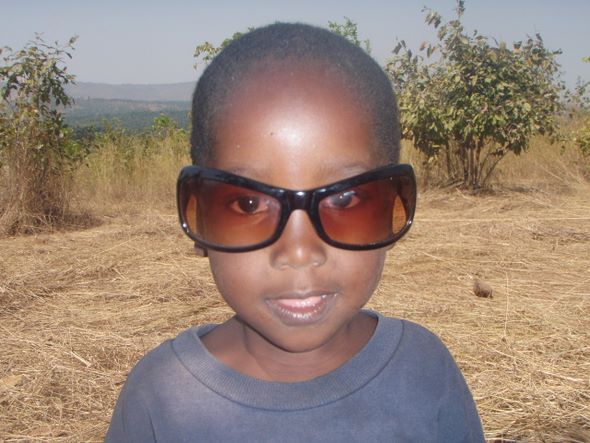

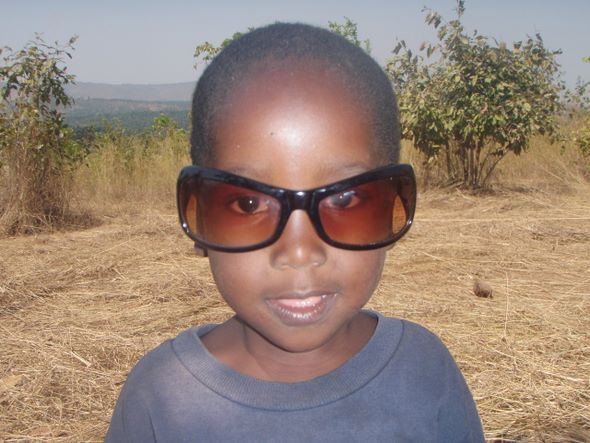

Seeing mama warm, clean and fed and baby self-soothing on the bed next to her was calming and lovely. Mama Nasula went home to eat and sleep. Jane and I took our leave. Mama Aziza’s mother stayed with her. The next day, Mama Aziza and baby were doing great! She asked me to take a picture and again said, Asante Sana. I told her I was so happy to help. I wish I had known how to say humbled, honored, mind-blown – but happy would have to suffice.

In the end, everything worked out fine for Mama Aziza and baby boy, Ismael. But, this isn’t always the case. They are lucky to have the talented Mama Nasula, but even she uses practices that could lead to risk. And, she can’t do much in the case of obstructed labor or other complications. My heart aches for the young beautiful women who die in labor or lose their children. My heart aches for their husbands and families. Fortunately, this was a happy story!

Hongera sana, Mama Aziza!! Karibu, Ismael!